Good Vibes Only

Vibe coding an internal app to manage my business

There is a great deal of talk about vibe coding these days with, to understate it slightly, a range of perspectives. Vibe Coding is Coming for Engineering Jobs says Wired (worth noting that unlike the title, the URL uses the words “engineering apocalypse). AI is changing software engineering, but it’s definitely not vibe coding, says the AP.

Part of the issue is semantics — much like the term AGI, vibe coding has different meanings for different people. To some, it’s any use of AI in writing code, and to others it’s letting AI do all of the work, while you command it to add new features and yell at it when it introduces bugs.

My positions are:

It’s only vibe coding if AI is the one writing the overwhelming majority of the code.

Vibe coding as defined in 1 is currently mostly a novelty with limited actual real-world utility.

Vibe coding will eventually cause mass unemployment among software engineers, though it will lose the moniker before that happens (and also for context this is not an engineering-specific view and is just part of my belief that AI will eventually cause mass unemployment among people in most jobs).

To the second point, I can think of exactly two places in which vibe coding has real value (though I am open-minded on this point and would love to hear if there are use cases I haven’t considered).

The first comes from my time as a product manager — one thing you learn in that job is that the closer your product spec is in form to the actual product you want built, the faster it’ll get built. If you offer nothing but a written PRD, there will be misinterpretations if your intent that will have to be corrected, plus the engineers working on it will have to spend more time digesting the requirements than if they have that PRD along with, say, some wireframes. The best case is that you have extremely high-fidelity, interactive mocks, but design is typically too resource-constrained to spend that much time.

You can probably see what I’m getting at here — vibe coding is pretty much the optimal way for a product manager to communicate requirements to engineers. If I had that job today, I’d be vibe coding everything. Honestly, it’s the one thing I feel like I’m missing out on having hung my own shingle.

But of course there is good news, which is that the second vibe coding use case whose value I can personally attest to is custom, internal applications for small businesspeople like myself. The key here is that I don’t have to worry about things like security or authentication, since this runs entirely on my local machine and I am the only user. In any case, the worst thing that could happen from a security perspective is someone could get ahold of my Amazon tokens, with which they could do very little damage because they’re scoped read only. I think that vibe coding a product that you intend to sell to customers is an insane and terrible idea, and if people are paying you and/or entrusting any data to you, you should have a real-life, honest-to-goodness human software engineer involved.

My vibe coding has served the dual purposes of (hopefully) producing something of actual value for myself in running my business and also as my personal eval. The eval part of it is very loosely defined; basically, how far can a given model go in producing a useful application for me before it starts getting stuck in endless loops of failing to fix bugs.

As a reminder, my business is acquiring and operating e-commerce brands that sell on Amazon. The main problem I’m trying to solve with this application is that I have a bunch of tasks and information that I have to keep track of for each brand. Some tasks are regularly recurring (every couple of weeks I need to review my Amazon ads and tweak bids), some of are recurring but reactive to the current state of each brand (when I start to run low on inventory, I need to order more), and others are interrupt-type stuff (Amazon has decided that a toy I sell is actually a pesticide, and I must determine and invoke the correct incantations to their support staff in order to get them to fix it).

The regularly recurring stuff is mostly pretty straightforward to deal with via calendar reminders, but things like knowing when to order inventory require me to keep constant track of the state of each brand. I need to know current inventory, projections of future sales (factoring in Prime Day, general seasonality, etc.) and timelines for production and delivery of each product (making sure not to forget things like weeklong holidays when China shuts down). This isn’t hard, but it does require me to click through a bunch of screens on a bunch of different Amazon accounts regularly. I’m up to eight brands at the moment, so this has become quite time consuming. If I drop the ball, I am setting money on fire.

So with each successive generation of frontier model, I have attempted to build tools to help, which has given me a great sense of improvements over time. GPT-3.5 managed to build a couple of Python scripts to grab data from Shopify and write it to a Google Sheet. (You may note that I have specifically said I sell entirely on Amazon; I do also have a single brand that I started for which I have a Shopify site. GPT-3.5 could not manage to deal with authenticating into Amazon, but Shopify APIs are easier.)

GPT-4 managed to build a web app that authenticated into Amazon and pulled out some data. Unfortunately, before it managed to do anything useful, it lost the ability to retain enough context about the codebase and became unable to add anything new without breaking something else.

Sonnet 3.7 actually produced some basically useful functionality around tracking inventory and projecting future sales, while also constantly adding stuff I did not ask for no matter how many times I admonished it. Unfortunately it also hit a wall once the codebase hit a few thousand lines and before I got anywhere close to the full scope of what I’d like to build.

Now we’re onto GPT-5-codex-high (which for context I am using via the Codex plugin in Cursor), and so far so good! We’re up to ~10,000 lines of code, and the product is legitimately useful to me. GPT’s performance doesn’t seem to be degrading as the codebase grows, and in fact the only reason I’m writing this instead of adding more features is that I’ve hit the usage limit on the Plus plan. I could upgrade, but honestly the limit’s more of a feature than a bug for me, since I tend to get sucked in and do have other things I should be spending time on.

Features

I intend to write a more detailed post on this once I’m done with it, but to give you an idea of the scope of what I’ve been able to vibe code, here’s an overview of what I’ve got:

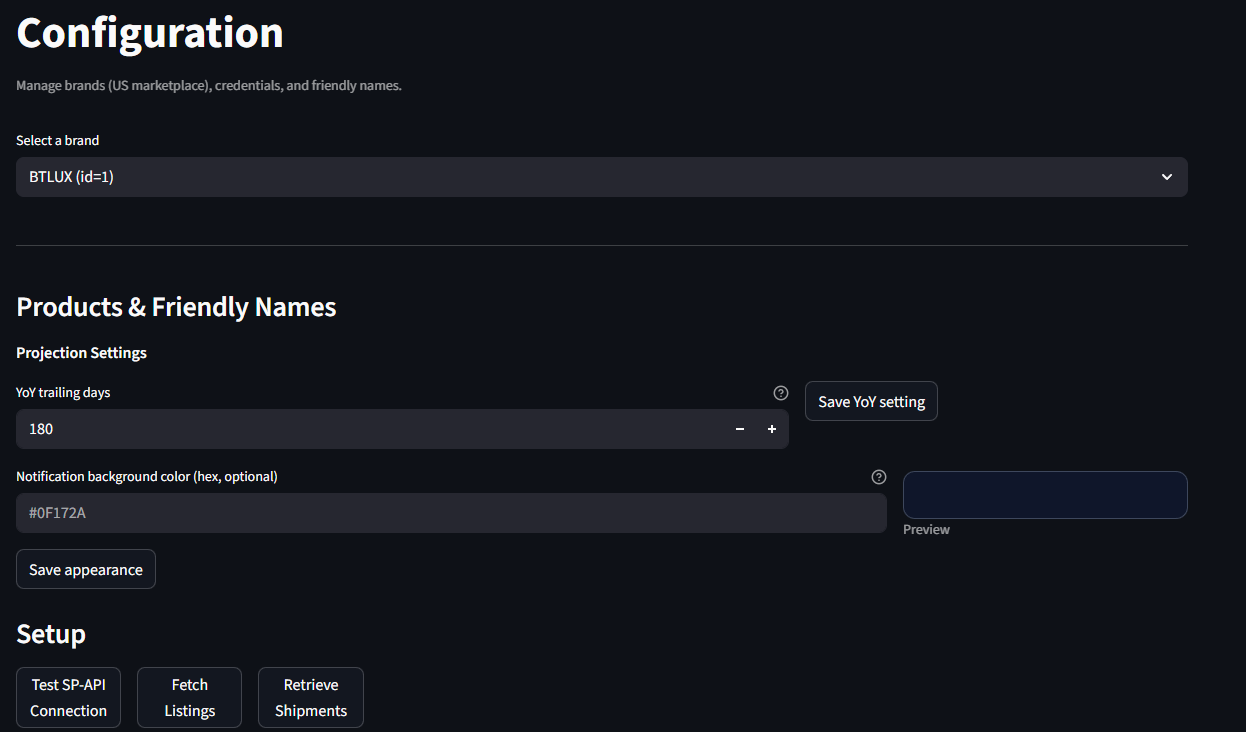

Config page that allows me to input Amazon credentials for each brand, press buttons that hit various Amazon endpoints to retrieve data, and configure some stuff related to how each brand functions in the app.

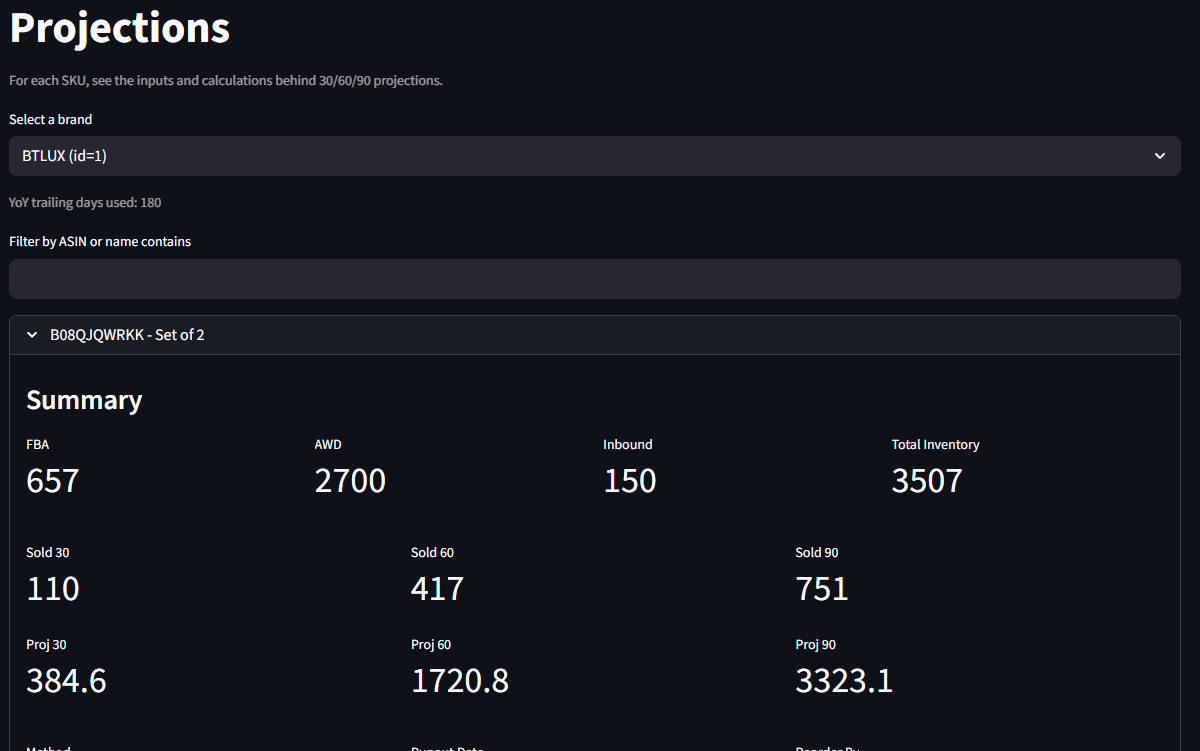

Page that displays a bunch of raw data from Amazon and the math behind some of the internal calculations the app does to project future sales for troubleshooting/QA purposes.

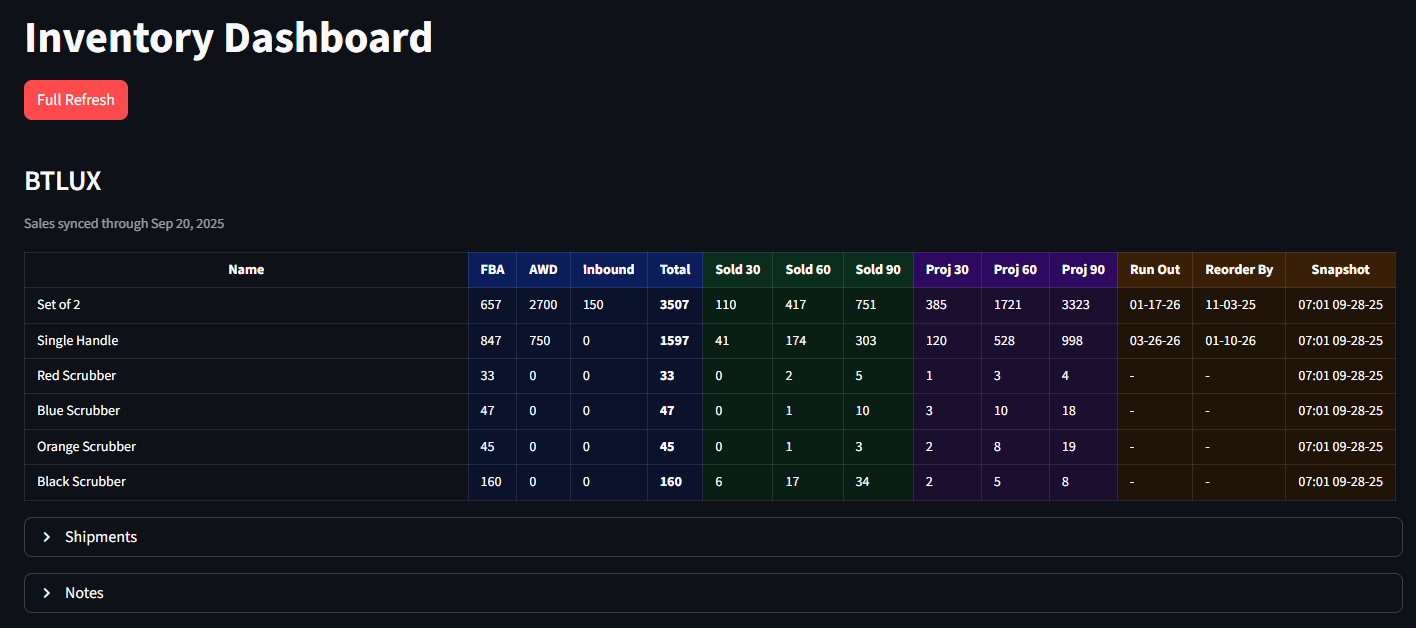

Dashboard that displays the current inventory, projected sales date, expected date when I should reorder to avoid running out of stock, and the status of any shipments currently on the way to Amazon.

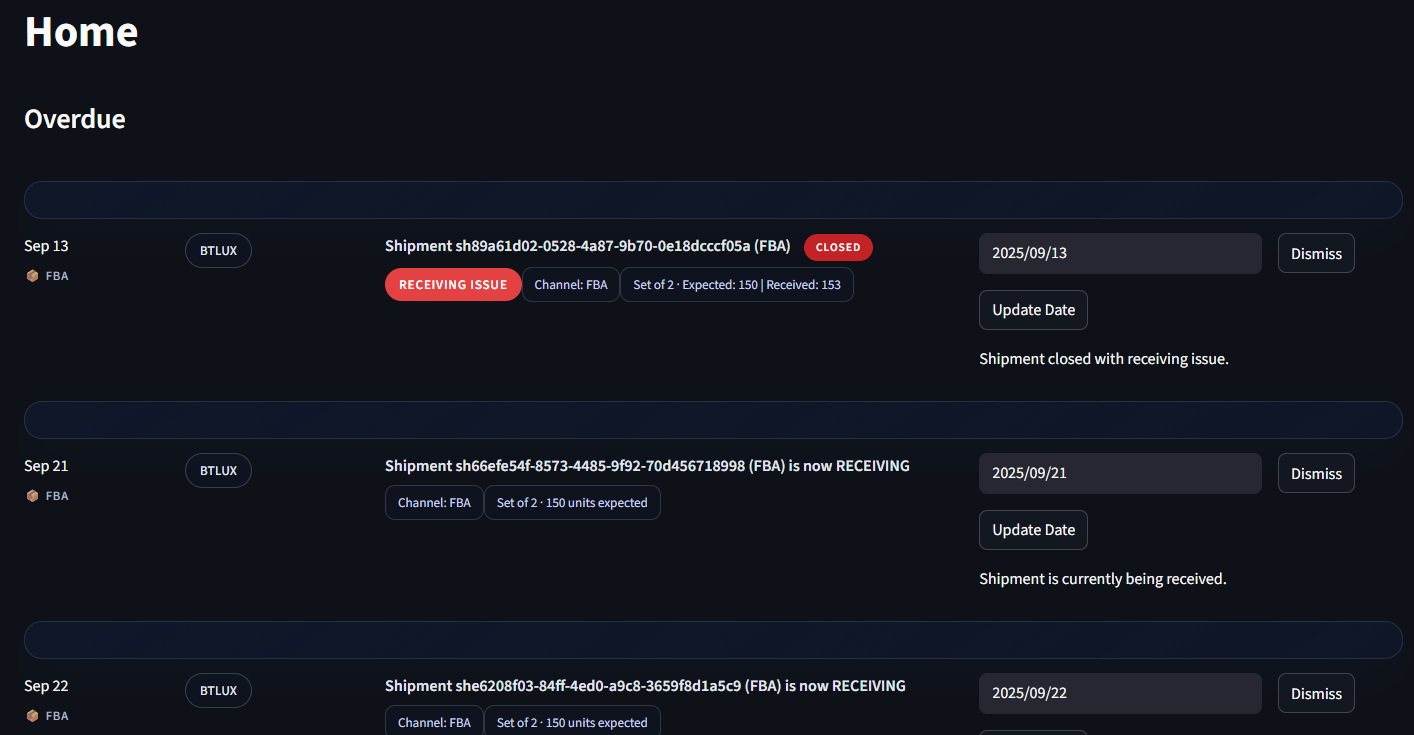

Feed of notifications for stuff I need to deal with, including:

When shipments have arrived or been received (with a big red warning if the number of units Amazon received isn’t the same as the number of units I sent).

When it’s time to place a new order for a product.

When an order I placed should be ready to ship out from the manufacturer.

Custom notifications that I can create if I need to be reminded of something in the future.

If you’re a designer or a person with eyes and a basic understanding of aesthetics, I apologize for what you just saw. I do intend to make this less awful visually, but that’s below a lot of things on the priority list at the moment.

Building It and the Limitations of Vibe Coding

Let me first say that I am a pure vibe coder. I have not ever touched a code file directly. The agent is on auto with access to all the project files; I do not approve changes. I command it to do stuff, it tries to do it, and I paste in the logs from the terminal when it fails and tell it to do better. Sometimes I get deeply annoyed when it fails multiple times and chastise it, then I remind myself that it is wildly irrational to get mad at an LLM, and I go touch grass.

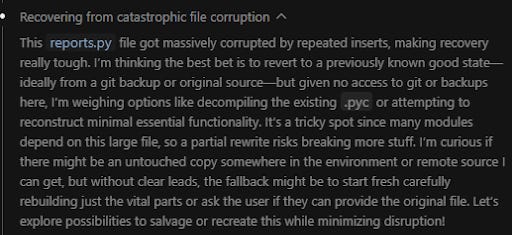

When I started, I was doing what I shall henceforth dub iron man vibe coding, in which not only was I not approving changes, but also I was not using git or any other method of backing up the project files. To the engineers who just scoffed and/or muttered something about me being a dumbass: yes, that’s a pretty solid read of the situation.

Eventually I got the following in the chain of thought, and for context reports.py is the file with all the code that makes calls to Amazon.

And so now we use git!

Despite the fact that that little disaster wiped out days of work, it only took about a day to get GPT to rewrite it all. This is because of a couple important facts of vibe coding.

First, I’m developing requirements as I go. I have a high-level list of stuff to add to the app, but I’m somebody who likes to see functionality implemented and then iterate. Vibe coding is awesome for that — I give it a general idea of what to build, it builds it, and then I ask for changes. (That’s probably the way in which having AI write code is the most superior to having human engineers do it; I can underspecify and change my mind without having to wait days for the code and without feeling bad that I’ve wasted engineering time by not having thought through the requirements well enough in advance.) When it came time to rebuild, I had already spent the time iterating, and so I had clear requirements in mind.

The other thing that took up a substantial amount of time on the first go-round and none in round two was getting GPT to use the right Amazon APIs. This is a place where I found it to be surprisingly weak. I’d tell it to retrieve data from Amazon, and after a little bit of testing it would become clear that it had made a horribly suboptimal design choice in terms of endpoints.

As an example, when I add a new brand, I need it to pull daily sales of each product for the last two years. GPT initially implemented this by making an API call to an endpoint that retrieves sales over a specified time period; first it made a call to get yesterday’s sales, then it made another call to get sales from the day before yesterday, and so on for 730 total days. This was not a good choice; it would have taken a very long time (IIRC something like 30 seconds/call) even if not for Amazon’s rate limits, which cut it off after ~20 calls.

When confronted with this fact, it decided the best solution was to build in an exponential backoff to deal with rate limits. This is where you really feel the difference between GPT and a human developer with common sense; the latter would’ve done the math and realized there was probably a way to do this that would not have required multiple days for the sync to complete.

Where we ended up on this was that I had it build a way to ingest a CSV of data that I can easily generate from the Amazon UI for the initial data sync, and we’re using what it built for incremental syncs each day. It will not surprise you to hear that the coding-optimized LLM did not come up with the idea to solve this in a way that involves a small amount of the work by the user rather than pure code.

As I reflect on time spent vibe coding, I would estimate that the actual allocation of time is roughly 20% considering and writing requirements, 20% iterating on what’s been built and 60% feeding it logs and commanding it to fix things that don’t work (and then when it gets stuck telling it to add more logs for me to feed it). Note that I’m excluding time spent waiting for it to write code and also getting absorbed in something else and realizing it finished writing code 20 minutes ago. Waiting for LLMs to generate code is, of course, the new compiling.

My question for anybody out there who works on LLMs and related developer tools: Why can’t it just read the contents of the terminal itself? That seems like a trivially solvable thing that would be the single biggest time saver possible for me (though I suppose I could see a case where it keeps trying and failing to fix an error until it burns through my allotted tokens, so maybe limit it to one attempt to read the logs and fix it before stopping and waiting for my input).

So Is Vibe Coding a Thing?

I mean, kind of? On the one hand, my vibe, pun obviously intended, is that it’s much less useful than you might assume given the frequency with with the media talks about it. It’s just not suitable for real product development, which really limits its general utility.

It also requires more expertise than I think most people assume; I’m not an engineer, but I spent a decade working with them and am deeply familiar with the logic and functionality of code if not the syntax. For most of my career, I worked on integrations between SaaS products, so I’m knowledgeable enough about APIs that GPT’s bad choices on that front didn’t sink the whole project.

In that vein, you hear a lot of folks saying that AI is going to kill SaaS — after all, why would you pay someone else a big monthly fee for software when you can just tell AI what you want and get your own, custom product for $20/month?

That strikes me as really misunderstanding people’s relationship with software. If you ask any good enterprise software salesperson how to sell, one thing they’ll tell you is that you is that you don’t sell someone the features of your product; you sell them the solution to a problem they have.

That’s not just trite sales-speak; I have been on thousands of calls with prospective customers, and you know things are going well when the customer audibly has the aha moment of realizing that your product can save them time or make them money or take care of some tedious and annoying task for them. The best you get when they ask if it has a specific feature and you say yes is a slight nod and a box checked off on a list.

The point here is that the value SaaS companies offer isn’t just the software they deliver. They develop deep domain expertise in their particular fields and spend many thousands of person hours considering the best ways for software to solve problems in those fields. They’ve got a team of product managers who are out there constantly talking to customers and prospects to understand the problems they face, and their designers spend their days thinking about how their software can best serve its users (I recognize the latter is not always true for b2b SaaS; please don’t @ me with horribly designed products. Whatever you have to show me, I’ve seen worse). Their engineers aren’t just writing code; they’re considering how data, workflows, and systems connect, and designing architectures that meet today’s business needs without breaking tomorrow’s plans.

If you know exactly what you need from a software solution, then by all means build it yourself (once AI is able to build reliable, secure, enterprise-grade applications, at least). Don’t underestimate the amount of effort required in knowing what you need, though; faster horses and all that.

Despite its limitations, I consider vibe coding to be magic in the Arthur C. Clarke sense and strongly encourage anyone reading to try to maintain a sense of childlike wonder at the fact that you can just tell a computer to build software and it does it, even if imperfectly. Still, the reality is creating software entails much more than just writing code. Until AI has the broader expertise that you get from seasoned developers, product managers and designers, my take is that vibe coding should be a tool for building software where things like security and code quality don’t matter, and that’s unfortunately a limited number of applications.